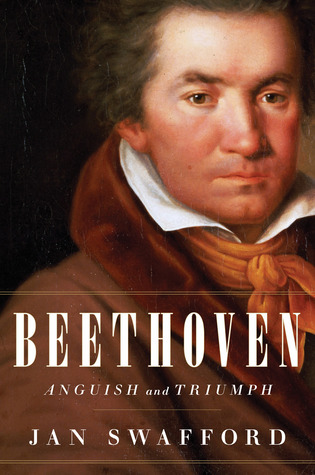

A good biography allows the readers to discover the person described as well as learn more about themselves and humanity in general. Jan Swafford’s Beethoven. Anguish and Triumph (Houghton Mifflin, Harcourt, 2014, pp. 1077)) is just such biography. Although written from the perspective of a writer who is also a composer, the book places Ludwig van Beethoven in his historical setting, describes his family life, and his composing process, and, above all, sheds some of the mythical encrustations that history has layered on this musical genius. After having read this biography, I have a much more nuanced and corrected view of the composer, and I appreciate his music so much more than before. Rather than attempting to analyze the book chapter by chapter, I chose to concentrate on three ideas that form sort of a background of how I understand Beethoven, humanity, and myself.

Beethoven’s tears

The book reports a visit to Beethoven’s family when he was very young, during which the visitor saw small Ludwig standing on a stool, playing the piano, and crying, with his father looming over the little child. This picture conjured many questions in my mind, least of which about how children have been and are “educated”. It is an idle and useless speculation to ask whether the composer would have been as great as he was without his early forced instruction in piano playing. But it is entirely possible that this experience molded Beethoven’s thought, often expressed in the biography, that “Difficult is good”. In other words, the composer put forward in his mind a challenge to himself: he made difficulty a driving force which helped him to overcome the obstacles that for us would seem insurmountable, such as his constant health crises, financial situation, sentimental problems, family troubles, etc. When a Scottish publisher asks Beethoven to make his original versions of Scottish songs easier for the young ladies to play them, Beethoven is recalcitrant. On other occasions, when orchestra members complained to him that his music is too difficult to play, he only says ‘go home and practice’. His attitude that ‘difficult is good’ is illustrated throughout his life. He does not complain excessively about anything: his health, his financial situation, his sentimental problems, his family troubles, and there were many of each almost constantly. It is more than Freudian “sublimation”, it is an attitude that the test one puts oneself in has a solution which comes from deep inside. It is a truly admirable stance, one that could help humanity to solve the problems we are facing, both at the individual and the general level.

Rossini’s tears

Gioacchino Rossini visited Beethoven in 1822. Swafford writes:

“Rossini was stunned by two things in that visit: the squalor of the rooms and the warmth with which Beethoven greeted this rival who he knew was eclipsing him. There was no conversation; Beethoven could not make out a word Rossini said. But Beethoven congratulated him for The Barber of Seville. … Rossini left in tears. That night he was the prize guest of a party at Prince Metternich’s. He pleaded with the assembled aristocrats, saying something must be done for the “greatest genius of the age.” They brushed him off. Beethoven is crazy, misanthropic, they said. His misery is his own doing.” (p. 751)

This episode plainly illustrates two things: one, that the compassion of an individual is not enough to be of any lasting consequence, and two, that the most contemptible answer to someone else’s difficulties is to blame solely the individual themselves. We don’t know if Rossini (or for that matter anyone else) provided some financial support to the composer. On the other hand, it is as if the aristocrats’ views provide us with connections to Beethoven’s political – quasi democratic/egalitarian – beliefs about the upper classes, their falseness, aloofness, and hypocrisy. Growing up in Bonn during the Enlightenment, reading German poetry, encountering other composers, taught Beethoven about political ideologies, about possible changes in the world, and about the power of some individuals to affect changes. Seeing this episode from a contemporary perspective and comparing it to prevailing attitudes today illustrates the fact that we still have to learn a lot about equality, both at the individual level, and at the general level. It’s enough to see how the majority of the US citizens and their political parties fear, dread, and are terrified by egalitarian thoughts. As I have written elsewhere, universal income could be the answer to most of the social and economic problems, but this solution is not acceptable nowadays.

“To keep the whole in view”

One of the three epigraphs that Swafford offers after the title page of her biography is by Beethoven. She does not indicate where it comes from. It reads

“My custom even when I am composing instrumental music is always to keep the whole in view”.

In composing, therefore, Beethoven had a firm theme which had to fit in the whole composition, and Swafford gives numerous examples how that pans out in his oeuvre. What I found interesting is the word even, because it indicates that Beethoven, when doing/thinking anything, kept “the whole in view”. My interpretation is that he took account of what nowadays can be called the context. It seems that he was not rash in his judgement of people (even though he was wrong about Napoleon); he was widely read and his ideas stemmed not exclusively from the Enlightenment. He held high ideals which he translated into music. It is clear that humanity needs lofty ideals, of which there is dearth at present. But more than that, we need to keep the whole in view, keep asking about the context in which certain events happen, whether they be individual or national or general. But for that we need an education that does not focus on jobs, perpetuating therefore the capitalist hegemony.

In conclusion, this biography provides ample opportunity to learn about Ludwig van Beethoven, about the political, economic, and historical context of his life. But it also offers a lot of possibilities to look at one individual’s life with a compassionate outlook that is not judgmental. Above all, it teaches us more about ourselves and out humanity.