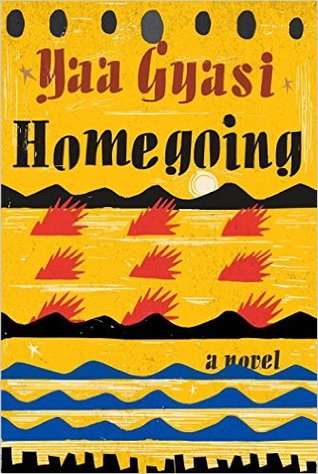

If ever there was need to describe in words the various incarnations of evil and hate people show for each other and toward themselves, this need has been satisfied by Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing (Penguin, 2016). The novel follows the history of 2 families (through 8 generations) of Asante/Fante peoples both in Ghana and in the United States, where some were brought as slaves as early as the late 1700s.

The stories of the characters offer a quick, honest, and simple read. The themes of these stories echo themes found in most narratives which deal with the search for ancestors, search for the purpose of one’s existence, and the role of the family, subject matters dear to second, third, fourth generations of “Americans”*: the case of “Italian American” narratives comes to mind readily. The elaborations of three ideas stand out from the novel’s flow: the iterations of ferocity, the lack of a solid definition of home, and the role of ancestors.

The iterations of ferocity, evil, and hate span the whole gamut of human experience shown in the novel: mother against children, step-mother against step-daughter, husband against wife, chief of the tribe against his subjects, tribe against tribe, British against Asante, “Americans” against “African Americans”*, men against women, etc. Even though some characters in the novel attempt to offer a different reaction to violence and evil (such as suggesting not to increase the number of weapons, or falling in love with someone who may be regarded as “the enemy”), in the final analysis, the existence of ferocity and evil for ever is almost guaranteed by the novel. Some evil, mostly realized as hate (and therefore spawning violence), has roots in culture (the Asante tradition of not trusting an individual who is an orphan of an unknown mother), other ferocity stems from the feeling of superiority (Asante tribes feeling superior to other tribes – and vice versa, the British feeling superior to the Asante – and vice versa), other evil originates in exploitation, racism, discrimination, dehumanization (African slaves in the US a hundred years ago, “African Americans” in New York today). There is, moreover, another type of violence, that of being perpetrated on oneself, and in the novel, this is the one that results from the economic, political, cultural environment in which the individual lives: as one character says, “I am nobody from nowhere”: a statement which determines her uneasy relationship with the tribe. But the novel is not all about viciousness, ferocity, hatred, violence; there is also love between men and women, parents and children, grandchildren and grandmothers. This reciprocal love, however, does not reach tribal or national levels.

Despite the title (“Homegoing”), “home” is an elusive concept throughout the novel, never receiving a full treatment. No character seems to have a “home” in the dictionary definition of the term, i.e.” a place where one lives permanently”. The closest to “home” is of course the nostalgic feeling for a traditional way of life in an Asante village, but one can be uprooted even from there by a rival tribe looking for slaves, or a British slave trader, or a desire to emigrate to the US. The uprootedness is exacerbated by modernity, where ex-slaves, “African American” mine workers, poor “African Americans” reel as corks in the enormity of economic, political, social, psychological ocean. So “homegoing” means going back to purported ancestral home, even if that may be vastly different in reality from the nostalgic, spiritual, attractive notion the homegoing characters have of it. The search for the ancestral home does not include the idea that this is the village that “evil had built”, as one character claims.

The role of the ancestors and ancestral land is crucial in the novel. Only through ancestors and ancestral lands characters can come to terms with themselves, their fears (of the ocean, of fire), their lack of motivation (of completing their PhD), their search for love. Interestingly enough, this role of ancestry and ancestral lands is eerily similar to that found by a study of second-generation “Italian Americans”: according to the Italian immigrant parents of the 1940s, their children have been pushed out of the paradise of the ancestral land where everything was like paradise and everything was in its place, so the experience was meaningful. In the novel, this picture of the ancestral paradise sustains the imagination and builds meaningfulness into the “homeless” characters’ lives. In this sense, “homegoing” has the function of supporting their understanding of identity enveloped in mystery and spiritualism. Ancestors, of course, being full of mystery, increase their status as image-makers, and echoes of spiritualism span centuries: spirits of mothers who, subjected to visions of fire bringing death and destruction, destroy the lives of their children and their own; spirits of slaves who died during the trans-Atlantic voyage, whose laments are heard across the centuries and are part an parcel of the water in the ocean.

In conclusion, the novel is a good, fast read. At times, however, it has the quality of an anthropological study of a culture whose details elude the researcher, but these are supplanted by the author’s skillful interweaving of magical and spiritual threads. If art is the search for the understanding of oneself, and verbal art makes this search so much more varied, it is not entirely clear whether the author has found the route to herself and her identity through the novel. Perhaps the sequel to this novel may answer this query. Admittedly, the most interesting aspect of the novel is left unsaid: the fate of the two characters who in fact engage in “homegoing”, albeit ending up in a resort at Cape Coast, where they finally let go of their fears (she of fire, he of the ocean) rather than finding solace and answers at a village family compound.

—

*The quotation marks in words and phrases such as “American”, “African American”, “Italian American” simply denote the frustrating vagueness of these notions which are devoid of historical, sociological, political, psychological, or cultural context.