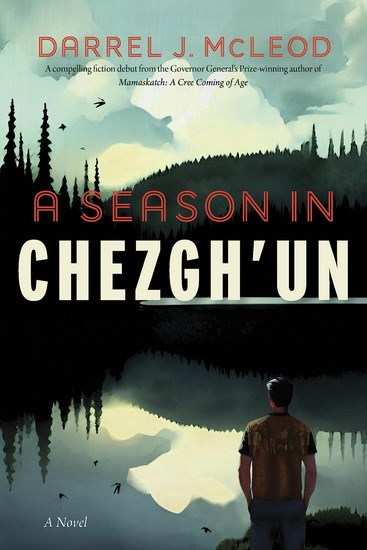

What adventures can a protagonist, self-identifying as a Cree, experience in the territory belonging to the Dakehl nation in Northern British Columbia as a school principal in the 2000s? Darrel J. McLeod’s character in A Season in Chezgh’un (Douglas&McIntyre 2013, pp. 320) undergoes a gamut of feelings, and a variety of expected and also unforeseen events. Although a fictional character, James not only gives the reader a really interesting and engaging look at the life stories of one of the First Nations people, but also provides numerous examples of emotions and events that closely resemble those of the characters in immigrant/Italian Canadian fiction.

James’s life story gives us examples of the atrocious history of abuse, maltreatment, neglect, discrimination of all First Nations peoples. Having experienced some of these, having lived without his father and with his alcoholic mother, having been caught in the web of sibling suicides and addiction, and suffering from sexual abuse by his white brother-in-law, James is, however, able to leave his Cree birthplace, study at the university, travel, enjoy varied cuisine, fashion, and music, live with his lover in a Vancouver apartment. All these experiences, however, not only make him insecure, but also extremely unhappy and he never feels that he belongs. He is aware of these negative pressures that his environment as well as himself put on him. And yet he does not give up: he compares himself to the sockeye salmon who leave fresh water to migrate great distances in the sea and then come back to their spawning grounds and die there. (p. 18) As an educator, he applies for, and receives, the position of a principal at a Dakehl school. His expectations (also muffled by his welcoming committee) soon make him realize that if he wants a real school, he has to build it himself. He is not undaunted as he joggles his ideas between the local/provincial school administrators and the elders of the community. He is truly happy when he sits at the shore of the lake and observes the wild life there or when he shares food with the Dakehl community, or when he participates in a ceremony with the tribe in a Mayan village. He is able to hire new, young staff, he promotes the cooperation with and experiential learning for the children and adults in his community. He observes the internal squabbles and the disagreements between and among the different tribes and is able to walk this tightrope with success, without making too strong enemies. His most successful projects are having the youth like the school, attend it and participate in all the activities, as well as having the elders take literacy classes that lead to participation in their political struggles. His feelings of being different in any and all circumstances are heightened because of his belonging to the gay community, with the concomitant fear of an HIV infection. He finds release from stress in sex. When he is offered to come and play the piano at the white neighbours, his answer illustrates not only his complex of inferiority but also his desperate need to be approved by others (p. 69):

“That’s generous, Louise. thank you.” James answered earnestly, although he knew he could never take her up on her offer. In addition to his shyness, his pride wouldn’t allow him to accept what felt like charity – the benevolence of someone in a position of privilege and wealth bestowed upon a lesser being. And then there was the optics of it all, if he were to be seen as being too cozy with the local gentrified white folks, what would the Native people he was working with think of him?

The novel concludes with James accepting another job and going to another post in Salmon Arm. On his way he swerves his car to avoid a beaver who nevertheless is injured; while James muses on the importance of this animal for his people, the animal jumps up and claws his thigh. The fact that beaver is also a national emblem of Canada, and this emblem injures him, is a clear metaphor for the impossibility for James to live in peace with his environment.

There is a metafictional element in A season in Chezgh’un when James reads Une saison dans la vie d’Emmanuel by Marie-Claire Blais (the use of the word “season” in Mcleod’s title is interesting). James notices that the novel “recounts a story of poverty and oppression in rural Quebec, and it comes as close as any mainstream piece of literature has to capturing the reality that James, his siblings and cousins grew up in.” (p. 31) Besides mixing reality and fiction, this metafictional detail in McLeod’s writing gives away one of the most troublesome perspectives that Canadian fiction can have for an author that does not deem himself to be a Canadian. The desire to become an author of “mainstream” fiction is great. In Native authors’ case, though, this is a struggle which they wrestle with more than any other “ethnic” Canadian author, since they do not identify with Canadian culture, whereas the “immigrant” authors have to.

Although a comparison between Native-Canadian and ethnic-Canadian writing requires a full treatment, I will concentrate here only on points of convergence between themes and tropes common to the Cree-Canadian and Italian-Canadian prose (the Cree-Canadian is represented by only one novel, though). Therefore there is no discussion of differences in topics such as sexual abuse of young children (in the Natives’ cases but not mentioned in the Italian Canadian case, although rape is present), or the abuse lived through in residential schools suffered by the Natives (Italians in Canadian schools, just like any other “ethic” pupils received other types of discrimination in schools). The following common themes in stand out:

- grappling with history: protagonists both Cree and Italian struggle to come to terms with the fact that they “lost” or are in fact losing the cultural certainties (language, beliefs, ancestors’ way of life, naming practices, etc.) which their ancestors had held for millennia.

- impossibility to belong to any group, “mainstream” or indeed to one’s own: blatant and covert discrimination makes this even more profound.

- intense desire to belong to the mainstream group, to be accepted and included, even though this desire clashes with the innermost feelings of the individual.

- ancient belief systems shattered, i.e. in the case of the First Nations the perpetrators are the Catholic nuns and priests, in the case of Italians, it is also the Catholic priests who do not allow or do not understand certain pre-Christian beliefs to be practiced.

- comparison with nature: James compares himself with the sockeye salmon, the trope in the Italian Canadian culture of the immigrant generations was the fig tree: it can survive in Canada, but it has to be bent out of shape and protected, covered in the winter.

In conclusion, A season in Chezgh’un underscores the necessity to go beyond the received truths about an individual’s life and their history. This is the lesson also from (Italian) Canadian fiction. And as we are now (2024) at the cusp of an unprecedented general cultural upheaval – the use of AI becoming so much more than simple aid to human life – what can the slash between pre-history and modernity teach us about the division between modernity (humanity, anthropocene) and bio-techno-world? If these processes can indeed be compared, humanity does not have much to rely on for support from the past. The two solitudes, representing Canadians and Natives/immigrants are truly becoming many solitudes.

___

*To be consistent, I should have written Molisan Canadian or Calabrian Canadian fiction to make it clear that the authors of Italian origin (or their ancestors) come from different parts of Italy, just like First Nations peoples come form different regions, and therefore have different cultures and languages. The Italian Canadian prose fiction which I base my comments on include Frank Paci’s Black Madonna, Nino Ricci’s Lives of the Saints, In a Glass House, Where she has gone. Poetry requires another post, but one can start here: https://www.tlnoriginals.com/title-item/invisible-voices/.