The sciences are those modes of inquiry which relay on quantification. If it cannot be quantified, it cannot be studied. And music is not an exception. Those who study the psychology of this art have at their disposal a variety of machinery and observational tactics with the purpose of quantifying the data. Here below are some of the most intriguing and thought-provoking quotations from Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis’ The Psychology of Music. A Very Short Introduction (Oxford U Press, 2019, pp. 121). These quotations are accompanied by my own take on the information they contain.

Usually, the quote that initiates talking about music in general is “Talking about music is like dancing about architecture” (source unknown). This is on account of the fact that human music is like no other phenomenon of modes of expression, reception, performance, composition. Therefore, the closest to what human can say about music is a simile, for ex., “Music is like language”. In my opinion, this is not really true and it does not give both modes the appropriate due.

p. 10 “Like language, music consists of the complex patterning of individual sound elements. Like language, music varies across human cultures. Like language, music occurs dynamically in time and it is capable of being notated. And arguably, like language, music seems to be unique to humans.” So the psychology of music relies on many of the theories and methods of linguistics. However, it is proving to be difficult to observe the perception and production of music in a natural setting. Much work needs to be done, notwithstanding the large corpora of data and the help of computer technology. One of the similarities discovered between music and language is the observation that people slow down at the end of spoken phrases, and performers also slow down at the end of musical phrases. However, the simile could also have been “Music is like clothing”, because clothing is also complexly patterned, varies across cultures. And this simile would also put forward the idea of homogenizing – both in clothing and in music.

p. 21 “Music is often perceived as expressive in ways that go beyond language. Music can seem deeply meaningful even when it does not denote a concrete object or idea; rather, it seems to traffic in the ambiguous, the multiple interpretable. … p. 22 “the sense of being transported beyond one’s self tends to be a hallmark of musical listening across the world. This powerful kind of experience has variously been referred to as effervescence, a surplus effect, or (in less fanciful terms) a heightened state of arousal. Rather than be listened to and merely received, music tends to sweep people into its vicissitudes, eliciting sympathetic movement (toe tap or head nods) of a tacit sense of participation (mentally singing along, or feeling drawn out of yourself and into the music). This capacity underlies …four primary functions of music: to regulate a mental of psychological state, to mediate between self and other, to function as symbols, and to help coordinate action.”

This is the most fascinating part of music: when you really listen or when you really play, it makes you feel like you are in another universe, in fact, it does away with your own self – the listener and the performer do not have a self. It is fascinating that this feeling of “outside-ness” is highly pleasant, and “waking up” from it is a let-down.

p. 22 the lullaby all over the world has the same features: higher pitch levels, slower pace, warmer vocal tone.

This is an interesting finding, given that musical traditions across the world use different materials to enact the four functions listed above.

p. 23 “Rather than depending on a single dedicated region [of the brain], the ability to hear, understand, and make music calls on networks spread throughout the brain – networks used by many other activities from speech to movement planning. This overlap likely explains some of the benefits musical experience and training can confer on abilities as diverse as learning a language, literacy, executive function, and social and emotional processing. … in other words, what might be special about music is not so much that it is different from everything else, but rather that it draws everything else together.”

This is a fascinating observation, underscoring the complexity of studying music in the brain.

p. 57 (musical grouping) “Because auditory sensory memory does not extend past about five seconds, it is difficult to directly experience rhythmic relationships that extend beyond this timescale. Larger-scale temporal relationships – such as form – tend to be perceived in a less sensory, more cognitive way.”

This is very interesting and it points to the idea that music does not simply touch the emotional phenomena, but involves the cognitive ones as well.

p. 60 (rhythmic patterns and language) “Musical themes from England and France…bear the marks of the linguistic environment in which they were composed: English themes contain more durational variability between successive notes, but durations in French themes are more uniform.”

This is a perfect example of how scientists leave the most interesting facts out of their description. Which music is the author talking about? Folkloric, vocal, classical, instrumental…? How exactly was this measured/quantified?

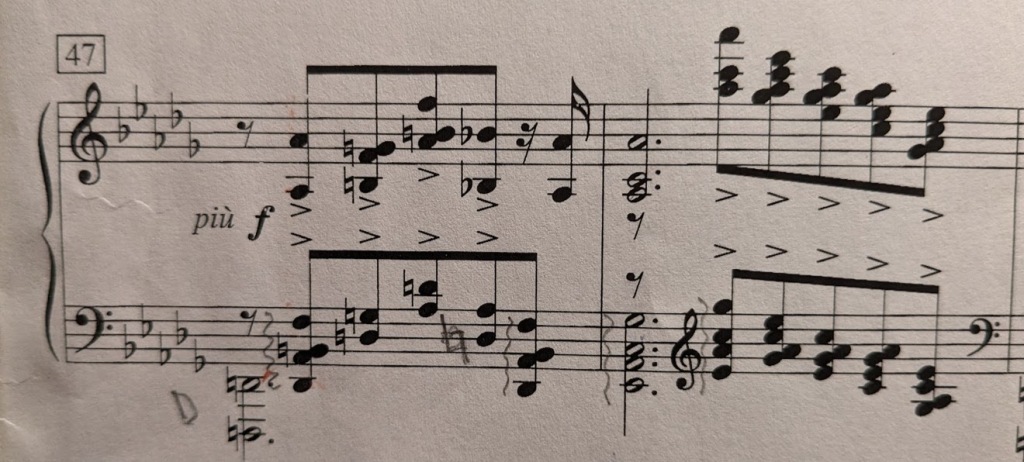

p. 63-64 “The dimensions available for performers to manipulate include timing…, dynamics…, articulation…, tempo… , intonation…, timbre… .”

All of these are amenable to quantification, so psychology has made big strides in this area.

68 “Understanding expressive performance is more about understanding the dynamic interplay between listener experiences and performer decisions than about understanding how performers relate to a score… .”

This is yet another unclear discovery: does it mean that the more the listeners knows the score, the more they can judge the subtle variations of performers? But then it means that listening in this way is more cognitively, not emotionally-driven.

69 there seems to be a difference between listeners’ enjoyment and interest.

Here, too, the author does not elaborate, especially as regards the definition of enjoyment and interest.

69-70 “Numerous studies show that information in the visual modality-particularly the movements of performers as they play – has powerful effect not just on the overall evaluation of the performance, but also on what listeners actually hear. “

This is called “perceptual illusion” and it was mostly examined by having a video recording of someone saying “ba-ba-ba” superimposed on a video recording of the lip movement for “ga-ga-ga”. People looking at the video tend to hear an in-between syllable such as “da-da-da” which corrects to “ba-ba’ba” as soon as they close their eyes. Apparently, “what the person sees can fundamentally shape what a person hears.” It is difficult to gage this experiment’s design and translate it to music and its visual reception. People were observed to rate dissonant moments in blues performances of B.B. King as more dissonant when accompanied by a video footage of him visually highlighting the tonal conflict. “Perceptions of dissonance contribute essentially to affective responses to music. Scholars have tried to explain them in terms of the structure of the human ear and basic psychoacoustic principles, but research suggests that even something like the raising or lowering of an eyebrow can play a role.” (p. 71)

71 “…musical expressivity can sometimes be more easily decoded from the visual than the auditory domain”.

The observations that give rise to this finding were of a violinist either playing very expressively or in a deadpan manner. However, there is no mention of being just too expressive, which may interefere with the enjoyment of the performance.

72 “People also tend to enjoy individual performances more if told they come from a world-renowned professional pianist rather than a conservatory student.”

This is an example of the power of the peripheral information about a live concert: this information determines already the mind-set of the listeners and predisposes them in a certain way to the experience.

73 “Most studies suggest that performers plan three to four notes into the future as they play. This span increases as people gain experience; the longer someone has studied an instrument, the more anticipatory errors they make. “

This is interesting: I has always been interested in knowing why i play the wrong notes. I have to start observing if the erroneous notes are in fact notes that I anticipated by playing them too early.

As regard practice, p. 75 “No other measure, including intelligence and a general musical aptitude test, was able to predict the success [of learning a piece]. More practice has been shown to lead to faster transitions from key to key in pianists and more consistency in expressive playing.”

In other words, there is no substitute for practice. Moreover, the type of practice is crucial: quality practice involves ” careful self-management, attention, goal-setting, and focus.” p. 75 And, interestingly enough, “some of the findings currently attributed to practice may ultimately prove to have their roots in biology”.

This is a fascinating finding, because it touches especially the inclination to practice, which seems to be inextricably connected to a function of the genetics of musicality. Further questions on musicality involve the variables that account for musical capacity and its acquisition, the level of inborn musicality, and its development. Research focuses on pitch perception (frequency of sound waves), tonality, exposure to different types of music, all possibly having to do with developmental stages, and effects of musical training.

p. 96 [as regards emotional responses to music] “It is important to distinguish between two kinds of experiences. On the one hand, music can evoke emotion. Listening to a song can lead a person to weep in sorrow or to experience great joy. But sometimes, rather than actually experiencing an emotional state, listening to a song might lead a person merely to recognize that the music is expressive of sorrow or joy. Although both of these responses are interesting, the first has received more attention from music psychology because it is so puzzling. emotions are usually inspired by clear events relevant to a person’s goal. For example, sorrow might be elicited by the prospect of abandonment and joy by the hope of reconciliation. Music cannot abandon someone or reconcile with them. It seems to carry no goal-relevant object that would render it capable of triggering an emotional response.”

It seems that we are hard-wired to respond to, for ex., sudden, loud, unpleasant sounds which ready a person to respond even in situations which prove to be innocuous.

p. 99 “Music may also elicit emotions by triggering visual imagery. People generate visual imagery and imagined stories easily in response to music.”

It would be helpful to examine if the composer’s imagery (if in fact there was one) relates closely to the listener’s imagery.

p. 100 “Most of these [associative and visual] mechanisms rely on music’s entanglement with nonmusical entities – the way music can reference particular experiences or objects or social groups. However, one mechanism – musical expectancy – depends more exclusively on the purely sonic aspect. …a theory links between moments of musical surprise with experiences of emotion and expressivity. …even listeners without formal training anticipate particular continuations as the music progresses. By deviating from these expectations – leaping to a far-away note or stepping out of the key – music can generate tension and expressive intensity.”

Researchers observed the duration and frequency of the emotional responses, the intensity of them, the propensity for them.

p. 103 “…studies reinforce the notion that people prefer music that occupies a sweet spot of complexity – music that is neither too simple nor too complex.”

Again, the author does not go into definitions of terms such as complex music or simple music.

p. 105 “The lifetime set of a person’s previous musical experiences and that person’s personality are not wholly independent variables, because personality influences genre preference. People high on openness to new experience tend to prefer genres they view as more complex, such as classical, jazz, and metal. Extroverts tend to prefer conventional genres such as pop, especially when the music is fast and danceable.”

The careful wording suggests that the answers were given by subjects self-reporting on their preferences. It is not clear what type of experiments were carried to come up with these conclusions.

p. 107 [Musical functions and motivation] “…categories of experience music affords or makes possible. Six basic candidates for these categories might include movement, play, communication, social bonding, emotion, and identity.”

Music, it has been repeated often in this book, resides and requires many areas of the brain to activate. And it links all types of external human activities,whether they are social, economic, physical, and individual, such as emotional responses and ability to concentrate. In the concluding paragraph, the author raises an urgent point:

p. 121 “By providing a laboratory for thinking between the sciences and the humanities, music psychology can fuel innovation that transcends its own disciplinary borders, while helping us understand a fundamental human attribute – musicality – that is key to our identity, our eccentricity, and our ability to understand one another.”

This is a heavy burden for one scientific discipline, and a project, if successful, which may actually help people understand not only each other but also, and especially, themselves.